Chasing sunsets is a hobby of mine, especially in the fall. This year, I brought along my new toy – a DJI Mavic 2 Pro – for the ride as I drove around east Tennessee and western North Carolina in hopes of capturing both fall color and a decent sunset in the same place on the same night. In doing so, I made plenty of mistakes (as usual), and thought I’d summarize some of what I learned and messed up so you hopefully don’t make the same mistakes I did.

- Scout, scout, scout. This is always important in terms of landscape photography, but is especially important in terms of drone photography. It’s important to know rules and regs about where you can and can’t fly / launch from, etc., and you’ll want to have a good idea of what you might be able to see from various vantage points. Google Maps (and specifically the 3D terrain feature) is a huge help here. Because you can fly, you don’t have to be as concerned about whether the view from a particular overlook is overgrown with trees such that a photographer with a tripod couldn’t get a decent shot – you just have to fly out 50 meters and you’ve got the perfect shot. The 3D Google Maps view does a great job of letting you see what’s possible.

- Check the weather. Nobody wants to drive 2 hours each way only to end up on-site and have the sky be solid overcast. Sometimes you can’t fully predict how the clouds are going to look (especially around here), but weather reports should be able to give you at least some idea. Check them frequently.

- Make sure your gear is in order. Multiple times I showed up on site with the phone I normally use for flying completely dead. Another time I ended up with a Mavic battery only charged to 60% because it had been knocked off the charger the night before. These are totally my fault. Don’t do these things. Check and double check to make sure you’ve got everything, and that everything is fully charged.

- Show up early. Again, this is important in any kind of landscape photography, but especially so for aerial photography. I try (where possible) to show up 1-1.5 hours before sunset, which gives me plenty of time to adjust to conditions on the fly.

- Take a test flight. No matter how well you’ve done your scouting, there’s a good chance things look different when you get there. I usually burn my first battery flying around the area, testing different compositions, looking for the shot I wanted. While in the air, I also look for different launch spots in the area that might be closer to the my final photo location I choose to minimize launch / recover time (see below).

- Have a backup plan. Even if you scouted well, there’s a good chance conditions won’t be perfect when you arrive. Maybe the clouds are further to the east or west than predicted. Before setting out, have some alternate spots you can reach (in time) if it looks like conditions will be better somewhere else (see also: show up early).

- Bring a computer to do some initial processing. This is one I didn’t do this season, but wish I had. If you shoot panoramas a lot (which I do) it can be hard to know how the overall composition is going to turn out by looking at the individual images. Is that road going to be framed where I want it? Should I move the drone a few hundred meters left or right? Would a different altitude help the composition? These are questions that can be hard to answer unless you have access to a computer and some quick photo editing. It’s worth having that ability, even if you don’t use it every time.

- Use the map on the controller. Once you’ve found your “final” spot for the night, erase the tracking on your map and note your altitude so you know where to go back to after battery swaps. This way, you can keep a fairly consistent look to your images, even though you’ll have to change batteries at least once.

- Minimize launch / recover time. This seems obvious, but is easy to forget in the moment. The more time you spend flying to / from your final photo spot during launch / recover, the less time you’re actually taking pictures. If you can go straight up in the air, or just 25-30m out beyond your launch site, you can spend almost the entire 25 minutes of battery life focused on photography, not on battery management / recovery. Sure, you fan fly half a mile to get to the perfect spot if you need to, but staying as close as possible helps tremendously with battery management (more on which below).

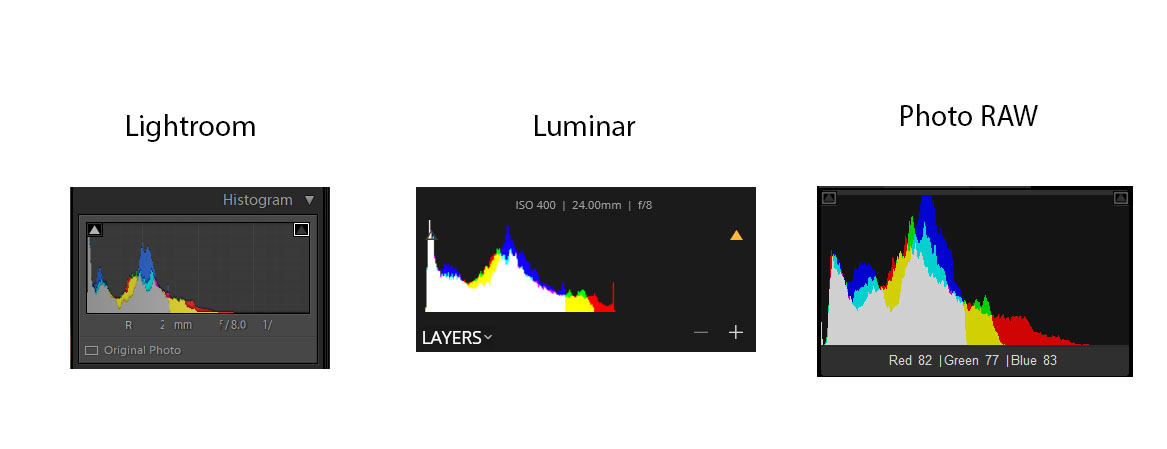

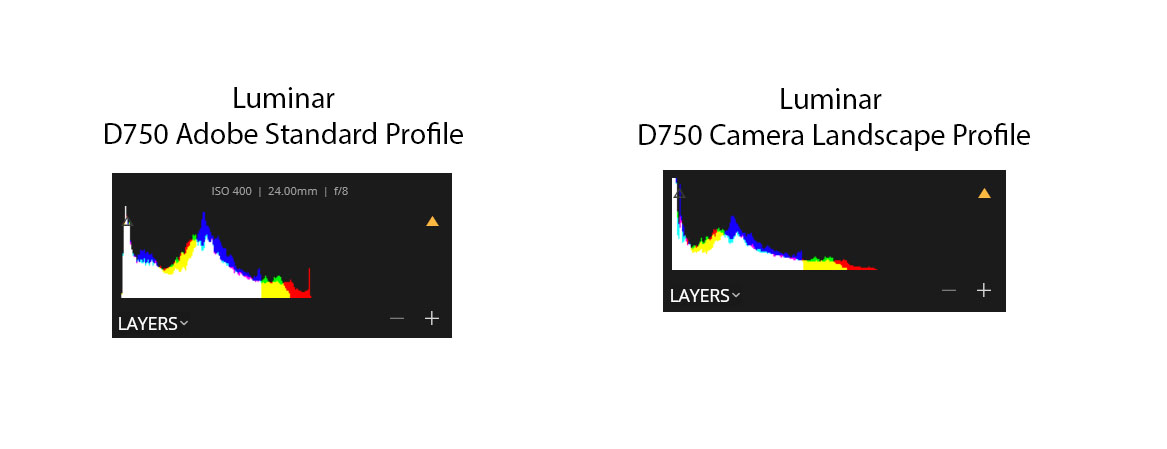

- Know your camera. Because the DJI’s sensor isn’t the most amazing in terms of dynamic range, exposing to the right is critical (even if you’re going to use HDR / exposure bracketing). Unfortunately, DJI seems to be quite conservative on their highlight clipping presentation in the app, which means you’re less likely to overexpose a shot, but more likely to underexpose one. This may be related to the 16-bit files the Mavic produces (even though I’m fairly sure it has only a 12-bit signal path), but highlight recovery is surprisingly good – good enough that I’m starting to push the exposures 0.7-1.3 EV over what I normally would, both for the center point of an AEB, or a single automatic panorama. The histogram (instead of the zebras) can be helpful here, though not definitive. More research needed :).

- Plan your battery swaps ahead of time, and keep a close eye on the clock. The worst thing you can do is be on the ground when the clouds light up overhead. Actually, worse than that would be to run out of battery and start recovery on battery 2 just as the clouds light up overhead. Don’t do that. Most of the action is going to be concentrated in the 10 minutes either side of the published sunset time. Therefore knowing what time the sun sets is crucial. From there, you can back out when you want to launch and recover. If, for example, sunset is at 1850, I would plan to launch my first flight sometime in the 1730-1745 range to fly the area and find my final photography spot for the evening. This would give me plenty of time to fly, shoot some test images, recover, analyze, and drive to another location if necessary. I don’t feel the need to use up my entire battery on this flight – in fact, if I don’t have to, I’d prefer to save it, just in case. But taking the test flight is usually a good idea. My second flight would probably launch at around 1815-1820. My goal in this flight would be to get on station, make any final adjustments, and get some initial shots of the sunset. This would depend somewhat on how the clouds are laid out – if it looked like a sunset that would have more action after the sun goes down, and if I knew my launch / recover time was very short (e.g. 1 minute) I might delay a bit and plan on a quick battery swap near sunset to give me more time between sunset and dusk. Usually, though, I’m timing this flight to be done at about 10 minutes before sunset. I try to time my final flight of the evening to launch about 7-10 minutes before published sunset. This gives me a good 10-15 minutes after sunset in case the clouds light up, and leaves me landing basically in the dark.

- Don’t leave too early. The real show often starts after the sun goes down. In a lot of cases, sunsets get worse before they get better. Sometimes they don’t get better, but in many cases the most rich and vibrant colors happen after the sun goes down (and after the color has diminished somewhat), not before. With a little experience you’ll learn when this is likely to be the case, but always stay on station several minutes after the sun “officially” goes down – you’re likely to be rewarded.

- Shooting panoramas: I typically tried to hedge my bets by using a couple of forms of shooting in camera. It turns out you can get some pretty good results with a single-layer, properly exposed panorama on the Mavic 2 Pro. The key there is “properly exposed” – and by properly exposed, I mean exposed as far to the right as you can get it without blowing out the highlights. The easiest way to get a decently exposed shot is to use AEB with a slightly over-exposed bias, as I mentioned above. My typical procedure is to take several AEB shots, interspersed with some shots taken using DJI’s automatic panorama mode (both horizontal and, more frequently, the 180-degree mode). For my own shots, I would typically use gimbal angles of +17 and -15, starting with the upper left shot, then zig-zagging across the frame (upper left, lower left, lower center, upper center, upper right, lower right), resulting in 2 rows, 3 columns of images. Using a 5 bracket AEB, this gives you 30 images in total. DJI’s auto panorama function can be used to shoot either a 9-image bracket (3×3) or a 21-image bracket (3×7) 180-degree panorama. DJI uses +18, -2, and -22 for its gimbal angles, so you can get approximately the same coverage with two rows (there are advantages and disadvantages to doing this). In the end, there’s no “right” way here – both work, and both have different strengths and weaknesses when it comes to processing.